A Conspiratorial Guide to the Irish Revolution

(Mis)understanding Irish radicalism on the British far-right, 1923

Recently, I have been interested in the question: how did the British far right understand Irish revolutionaries in the 1920s, particularly in an international context?

It would be an understatement to say that the Easter Rising of 1916 and the Russian Revolution of 1917 spooked British intelligence and establishment circles. But even more frightening was the prospect that the ‘Sinn Feiners’ and the Bolsheviks were heading towards an unholy alliance.

In March, Contemporary European History published an article of mine about the intimate side of one such alliance - a 1920s romance between an Irish socialist and a Latvian literary translator - and the ill-fated intelligence operation that ensued. The couple came under surveillance because British intelligence saw them as conduits of Irish and Russian revolutionary movements. The piece is available here in Open Access.

Returning to a still-tangled thread from this research, I thumbed through 1922 and 1923 issues of The Patriot, a conspiratorial magazine that emerged from the extremes of the British right in the 1920s. Among the journal’s contributors was one of Ireland’s own worst contributions to the 20th century: Sir Michael O’Dwyer, Tipperary-born apologist for the Amritsar massacre.

I came to the Patriot through a footnote that mentioned an investigation into a group called the ‘Irish Communist Brotherhood’ carried out by the magazine in a series of articles from 1923 titled ‘The Realities of Revolution’.

As a historian of the Irish radical world in these decades, I did not believe such a group as the Irish Communist Brotherhood existed. Having read the Patriot’s articles, I still don’t believe such a group existed. But I was not simply interested in debunking a century-old paranoid fable, but understanding its narrative pillars and what, if any, real people or events the Patriot saw as comprising this nefarious Brotherhood.

The answer was not all that surprising. The story of the Irish Communist Brotherhood was an antisemitic narrative tailored to Britain’s far right. The conspiracy sought to ‘explain’ the proliferation of radical groupings and insurrectionary events in revolutionary Ireland. However, instead of grappling with the actual ideas and issues which mobilised these movements and moments, the traditional targets of conspiratorial paranoia were conscripted into a murky tale of anonymised agents known only by their ethnic identities.

Take, for example, the Patriot’s explanation of the Brotherhood’s international network: a ‘prominent Jewish businessman’, readers were told, whose ‘ostensible occupation provides the reason for periodical trips between Russia and Ireland’ was Sinn Fein’s emissary to the Bolsheviks. A Jewish writer, ‘wife of a Jewish-Irish agitator’, was the businessman’s Soviet-based counterpart. The Patriot asserted that these activists, along with their ‘anti-British millionaire friends’ in the US and ‘German capitalists’, were primarily responsible for the tumult in Ireland.

As I discuss in the article linked above: migrants from the Russian empire did participate in Irish socialist movements. Irish people did move between Dublin and Soviet Moscow. There were marriages between Irish radicals and migrants from Eastern Europe. This does not imply a nefarious global conspiracy masterminded by a minority community.

What it actually suggests are the many forms of transnational collaboration enabled by modern communication networks and global travel, collaborations which built on emerging affinities between migrants and their host communities. Ultimately, these interactions were not central to the overall Irish revolutionary process. The Patriot, nonetheless, glimpsed Ireland’s early 20th century immigrant communities and saw an opportunity for a fear-mongering piece of propaganda.

The Patriot makes for troubling reading. You can’t help but wonder whether politicians with real power over people’s lives in Britain and Ireland were reading and believing it in the 1920s. The particular antisemitic trope that it repeatedly played upon in its coverage of Ireland and Russia, the myth of Judeo-Bolshevism, has had a long afterlife.

Although the advocates of these fantasies were usually isolated on the conspiratorial fringe, traces of the hateful tales that surfaced in the Patriot sometimes found their way into the broader political imagination. The wider influence of these conspiracies requires further research.

Reminds me of Voynich (nee Boole), her novel Gadfly galvanized opinion at the time of the Revolution and had considerable influence after. The Irish writer chose an Italian setting to inspire Revolutionary agitation in the Russian Empire.

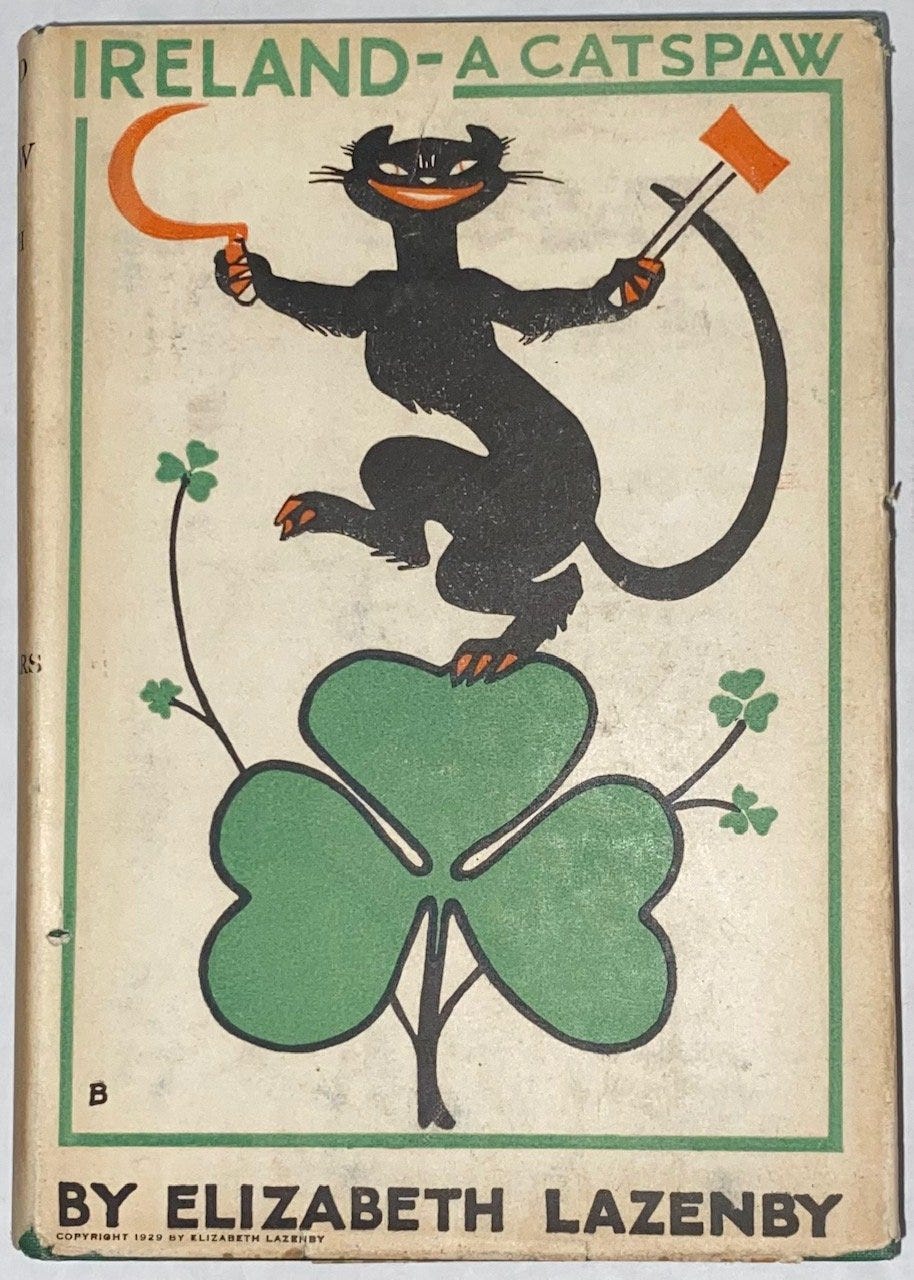

Is the illustration of Ireland as a "catspaw" of particular significance?

Could it have come from the IWW's "sabo-cat" black cat (which symobolized wildcat strikes)?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_Workers_of_the_World#/media/File:Anarchist_black_cat.svg