An African American Irish Abolitionist?

Lewis Sheridan Leary and the militant fight against slavery

I am convinced an Irish connection to every event in modern history can be discovered simply by staring at the sources long enough.

From the Irish in the Haitian Revolution to the Irishman who mentored Nelson Mandela, Irish names can be found on almost every side of the modern human story - and not always the right side.

Irish people get everywhere. It only requires a small expansion of your historical imagination to find them.

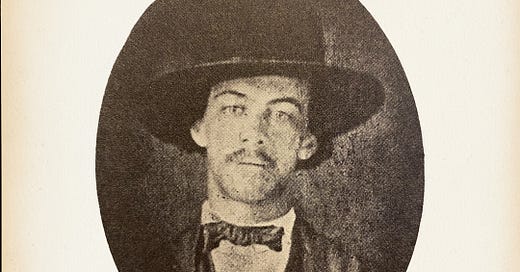

Let me explain with the case of Lewis Sheridan Leary (1835-1859), a figure who has a smaller role in African American history than he deserves and no place in Irish diaspora history, which has never considered him relevant to its story.

My interest in Lewis S. Leary began a few years ago when I watched the mini-series adaptation of James McBride’s wonderful novel The Good Lord Bird.

I’m almost ashamed to admit this was my first introduction to the story of John Brown, a militant abolitionist who decided decades before the American Civil War broke out that ending slavery in America by force was his God-given mission. Brown and his co-conspirators, which included some of his own children, sacrificed their lives for this cause.

In 1859, John Brown led a raid on Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, site of a large munitions cache, which Brown planned to capture and distribute to the nearby enslaved population. Brown planned to lead this army in a guerrilla struggle modelled on earlier slave rebellions, especially those of the Jamaican Maroons. The rebellion, Brown believed, would rapidly spread across the country.

The plan, of course, did not succeed (in the short term, at least). Brown’s rebellion was crushed, but the struggle entered abolitionist legend and was one catalyst of the American Civil War.

Fascinated by this event, I became determined to find the Irish link.

Reading the list of those who fought alongside John Brown in Harper’s Ferry I came across a name with a distinctly Hibernian ring: Lewis Sheridan Leary.

Aha, I thought, the Irish connection.

But the details of this connection would be more complex and fascinating than I could imagine. This find partly initiated a project I developed in collaboration with the African American Irish Diaspora Network. This project, an exhibition called Revolutionary Routes, transformed my own conceptions of ethnicity and identity in Irish diaspora history.

Lewis Sheridan Leary was, to tell a simple version of this story, one of the African American members of John Brown’s raiding party.

Lewis was born 17 March 1835, in Oberlin, Ohio. Recognise the date? Yes, St Patrick’s Day.

The Irish-seeming Sheridan part of his name is something of a red (or green?) herring: it was not tied to Irish ancestry, but allegedly honoured a ‘Mr. Sheridan who had freed his slaves.’ (This is noted in R. Greene’s 1989 family history The Leary-Evans: Ohio’s Free People of Colour).

The Leary name, however, does come from Irish family ancestry.

Sources differ on the precise nature of Lewis’ paternal ancestry: his paternal grandfather was a Jeremiah O’Leary, either described as Irish or part Irish and part Native American. His paternal grandmother was Sarah Jane Revels, described as either African American or part Native American and part African American.

Whatever way the accounts land, Lewis S. Leary is always described as a product of Irish, African American and Native American lines. Accounts usually simplify this by describing him with the marker by which his society interpreted him: as an African American.

If Leary were alive today, and his grandfather could be proven to be Irish born, Leary would be eligible for an Irish passport. He would certainly be eligible to be acclaimed as Irish on modern chat shows.

Does this make him eligible to be enlisted in the Irish diaspora story too, I wonder?

This is in part, why I am writing this post. I believe there is an important story about identity contained within the Leary family history. But my genealogical skills in this American History field are poor,.

Perhaps among Archive Rats subscribers there are those who can trace back beyond Lewis, even beyond Jeremiah and Sarah, to discover the truth of this Irish link.

If so, I would love to hear from you.

Over the summer, I paid a visit to Harper’s Ferry. I always like to visit places connected to my research.

It was meaningful to stand in the place where Lewis Sheridan Leary, John Brown and their comrades took a principled stand that still echoes today.

Just over 24 hours after the beginning of Brown’s raid in October 1859, Leary died from a bullet wound after being lifted from the Shenandoah, a river he had dived into in an attempt to retreat from the failed insurrection.

He was unceremoniously buried, alongside seven of his comrades, in a riverside mass grave. Later, this grave was exhumed and the men were given a more fitting resting place of honour on the Brown family farm in North Elba, New York State.

It is another destination I would love to visit, perhaps armed with a better understanding of precisely who Lewis Sheridan Leary was and which diaspora histories made him.

Another favour to ask…

This newsletter is free. But being a historian is not. Soon, my temporary academic contract will come to an end. I need your support now more than ever. There are two chief ways you can support me. The first is free and easy:

Vote for Hotel Lux in the Irish Book Awards. Polls close 5pm Dublin time, 14 November.

Don’t worry, you don’t need to vote in every category so it will only take a minute.

Secondly, you can pick up a copy of Hotel Lux at your favourite book store.

Already have a copy? Why not get that family member or friend who is feeling a little disenchanted at the moment a history book that should give them some political hope.

Interesting! Lovers of archives might enjoy these recent posts, including three interviews with archivists: https://janetsalmons.substack.com/p/archival-methods-for-online-researchers?r=410aa5 and https://janetsalmons.substack.com/p/it-is-academic-writing-month?r=410aa5