In the summer of 2021, I found hundreds of documents belonging to a revolutionary family in a shed by the Galician coast.

I was in Galicia for a specific purpose: to meet the grandson of Emmy Leonhard, a woman who was a key figure in my research.

Emmy Leonhard, an entirely obscure German revolutionary, lived in Moscow’s Hotel Lux from 1925-1926.

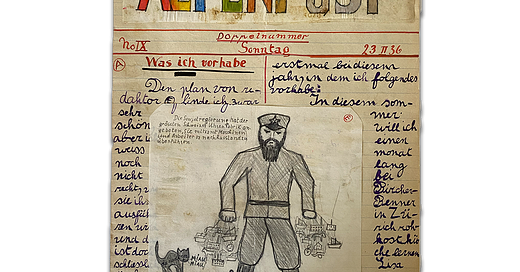

Before I arrived, Emmy Leonhard’s grandson Pedro shared with me some details of the family documents he inherited. One of the items, he told me on a video call, was a handcrafted newspaper created by his mother, Alida, and his aunt, Elisa, when they were children in the 1930s.

Accustomed from my own childhood to consider children’s art as veering on the Mark Rothko end of abstraction, I severely underestimated what I would find.

What I finally held in my hands was a beautifully illustrated and artfully crafted journal. It told a history of 1930s refugee life from the perspective of two absurdly precocious girls. Hundreds of pages had survived.

In this post, I will explore the most extraordinary historical source I have ever drawn upon in my work.

To make sense of the Alpenpost, this entirely unique children’s journal, you first need to know about the extraordinary family behind it.

Let’s meet the editors…

Calling these children ‘the editors’ is not my joke. Throughout its run, the two girls who crafted the Alpenpost always referred to themselves internally within its issues as the ‘editors’.

Elisa was born in Moscow in 1925. A few years later, she was joined by a sister, Alida, born in Berlin in 1928.

The girls’ earliest memories were formed in the German capital. Later in her life, Alida could still recall how much she and her older sister enjoyed visits from their mother’s friend Lev Sedov, the son of Leon Trotsky.

In 1933, following the Nazi rise to power, Emmy and the two girls clandestinely crossed the German-Dutch frontier. From the Netherlands, the trio eventually made it to Switzerland. Here, in 1935, Elisa and Alida began producing the Alpenpost.

… and the readers

Every issue of the Alpenpost is one-of-a-kind. It was not designed for a mass readership. It was created for Emmy and Edo, the parents of Elisa and Alida.

The girls’ mother Emmy Leonhard (neé von Kaemmerer) was born into a wealthy Hamburg banking family in 1890. She was elected to the Hamburg parliament as a social democrat shortly after the founding of the Weimar Republic.

While working as a translator in Amsterdam, she met and fell in love with Edo Fimmen, already prominent as the leader of the powerful International Transport Workers’ Federation.

Although Edo remained a social democrat, Emmy became a member of the German Communist Party. In 1925, she took up a role in the Communist International as a translator and was billeted to the Hotel Lux. When she left for Moscow she was already pregnant with Elisa.

After Emmy and baby Elisa’s return from Soviet Russia in 1926, Emmy sided with the Trotskyist opposition and rose to a leadership position within the movement in Berlin. A couple of years later, Edo and Emmy were expecting a child once more.

Meanwhile, Edo’s work took him around the world, from New York to Dublin to Tokyo. After Hitler’s rise to power and his family’s subsequent flight from Germany, he never again returned to Berlin.

As Emmy and the girls lived in exile in Switzerland, Edo, headquartered in Amsterdam, led an antifascist resistance network with operatives working across Europe and underground within Nazi Germany.

The Alpenpost, a handwritten weekly journal of family news, political analysis, puzzles and drawings became a means to bridge the separation.

In mid 1939, when Edo and his staff evacuated Amsterdam for London, rightly fearing an impending war, he took the entire collection of this newspaper with him.

You may recognise the style of the newspaper. I drew on Elisa and Alida’s aesthetic sensibilities for the design of this newsletter and my personal website.

The refugee routes of the Alpenpost

The survival of this newspaper allowed me to achieve something I thought almost impossible: to trace each precise step of the Leonhard family’s journey from their flight from Nazi Germany in 1933 to their arrival in Mexico in 1941.

But this children’s newspaper also let me piece together the social world of their refugee existence.

Certain ‘side-characters’ in the newspaper were major characters in the history of the interwar left. ‘Willi’ and ‘Babette’ for example were Babette Gross and Willi Münzenberg, major figures within Comintern politics who became prominent figures within anti-Stalinist and anti-Nazi circles in the late 1930s.

‘Simone’ was the closest thing the girls had to a consistent childhood friend: the French philosopher Simone Weil, who befriended their mother Emmy in 1934.

And then there were all the drawings that revealed Elisa and Alida’s attempt to make sense of a collapsing world and their parents’ efforts to prevent the coming disaster.

In these yellowing pages I found a skeleton key that unlocked the solution to a major research dilemma: how to trace the life of a family who, by merit of the real political dangers they faced, constantly abandoned their documents.

If I ever find anything like the Alpenpost again, it will be a miracle.

My Big News:

My book Hotel Lux is shortlisted for Hodges Figgis History Book of the Year at the Irish Book Awards. Please vote for Hotel Lux here. It only takes a minute and you don’t need to vote in every category. I really appreciate every single vote!